Sermon: "Broken Branches," Dec. 21, 2014

St. George’s United Church

December 21, 2014 – Fourth Sunday in Advent

Scripture: Matthew 1:1-17

“Broken Branches”

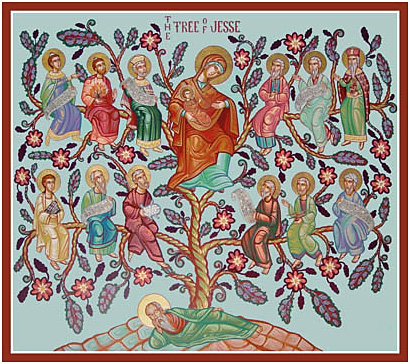

Nicholas Papas, The Tree of Jesse, St. Philip Antiochian Orthodox Church, Souderton, PA.

What a way to begin a story. Mark’s gospel begins in the thick of things with John the Baptist at the side of the river Jordan shouting “repent!” Luke’s gospel begins with a dedication to a faithful reader. John’s gospel begins cosmically, way back at the beginning of time with “in the beginning was the Word.” And Matthew’s gospel begins… with a list. A long, tediously precise list of names. Beginning with Abraham, the father of all nations. Through King David, Israel’s most celebrated King. On through the Babylonian exile. Name after name after name all the way down to Jesus. It might be the least exciting way to show someone your family tree.

A list like this can sound strand and confusing (boring?). But it’s here at the beginning of Matthew’s story of Jesus for a reason. In the ancient world heroes usually had long genealogies showing their heroic origins. Heroes didn’t come out of nowhere. They needed a lineage. It sounds a bit weird. But if you think about how much time and energy has been put in to trying to prove that Barack Obama wasn’t born in the United States, it makes a bit more sense. To be President, you need the credentials. Matthew is telling us that this guy, Jesus, has the right credentials. He has his own branch on the right family tree.

He’s royalty. Part of the family of King David, Israel’s most famous and beloved king. A symbol of Israel at the height of its power. Matthew tells us that Jesus is the long awaited king. The Messiah (the anointed one, the same title as David), who will restore his people to their former glory. And bring about a new golden age. Not only that, Jesus is also a son of Abraham. Abraham, who was promised to be the father of generations as numerous as the stars of heaven. And that the whole world, all people, would be blessed through him and his family. The king of Israel and the blessing to all nations. Jesus is a big deal. He’s going to make all things new. And he’s got the family tree to prove it!

Yet, like any family tree, if you go poking around enough you might find something unpleasant.[1] It’s chock full of shady characters. Men and women (mostly men) who have done just about every bad thing you could imagine. Abraham is the father of all nations and the receiver of the promise. But he comes within an inch of ending his only son’s life. His grandson Jacob grabs his branch on the family tree by tricking and cheating his blind father. Only to be cheated himself, fathering a son with the wrong girl because he thought she was someone else. Their son, Judah, mistakenly sleeps with his daughter-in-law Tamar who is pretending to be a prostitute. Then a few branches down, there’s Rahab. Who is an actual prostitute.

Then we come to David. David’s the ideal king, of course. His face is on all the money. But he’s also a ruthless bandit who unites the tribes of Israel in to a single nation by underhanded scheming and murder. Then he fathers Solomon, the next branch in the tree by Bathsheba, “the wife of Uriah” after planning her husband’s murder. Ahab and his son Ahaziah are sadistic tyrants. Almost the entire middle chunk of the family tree–fourteen generations–are stories filled with murder, lust, assassinations and military juntas. And are kings whose depravity is blamed for the downfall of the kingdom. Then comes Mary, an unwed teenage mother. And Joseph, the tradesman who plans to divorce her until the Holy Spirit intervenes in a dream. And Jesus is only on this tree because Joseph filled out his adoption papers! What a list! What a list!

By the time we come to Jesus, you realize that it really can’t get any worse. Matthew says that Jesus, the hero of the story, the Messiah, comes from a crooked tree. With plenty of broken branches and rotten apples. A family of murderers, liars, cheats, prostitutes, adulterers. Betrayers and illegitimate children. It’s a crazy way to start any story. Let alone one that claims to be “good news.”

It’s a crazy way to start a story. Especially at this time of the year. Because it seems to go so against the grain of the North American holiday season. By Remembrance Day bows and wreathes hang in store windows and Starbucks is brewing peppermint lattes. By late November, we hear the ho ho ho of jolly Santas and joyful soft-rock renditions of let it snow where ever we go. Our consumer society seems to be particularly good at hiding troubles and pain through purchasing. But it is no secret that this time of year, in spite of the cheer (or perhaps on account of the cheer for some) the pain comes out. This seems like the last time of year to start a story with Matthew’s family tree. But many, if not all of us, come from some kind of broken histories, broken families, broken lives. All of us live in a broken creation. Maybe you can spot your own story on one of the branches somewhere. And, much in the same way we fast-forward past Jesus’ genealogy in the Christmas story, we hope that the cheeriness of this season helps us forge ahead and forget that past. We hope it will help us make it through to New Years when we can make resolutions to become better people. Where we can leave the past behind. Where we can start again. Much like our own, Jesus’ family tree is the last place anybody would ever look for hope of any kind. It might as well have the word “hopeless” spray-painted across the trunk.

Strangely, though, this tree is the place that we are told by Matthew that the new start begins, that Christ comes in to. Here at the end of this long, messy list of generations. And maybe this is the point. The Messiah is born, not with a pure pedigree. Not to a perfect people with a spotless, untarnished past. Instead, God comes to an odd people with an extremely dysfunctional family tree in an extremely dysfunctional world. The late Catholic priest Herbert McCabe said that this family tree is Matthew’s way of saying that God’s work isn’t always accomplished by the most pious, spiritually enlightened people. But more often than not God’s work is done through “passionate and disreputable people.” Jesus, he tells us, didn’t belong to the clean, deodorized, censored version of the world. But of the world as it is. He “belonged to a family of murderers, cheats, cowards and adulterers and liars,” McCabe says. “He belonged to us,” he says. He “came to help us. […] and gave us some hope.”[2] Matthew tells us that this is the family tree that sprouts green shoots, new growth. Somehow, this group of imperfect, disreputable and often scandalous characters are where the new beginning comes. In Christ, God’s future appears to be coming, sprouting from the trunk of an old, rotten tree.

If God can work through a family tree like this, what about our own? What about our own pasts, our own histories? Jesus’ family tree is divided into three groups of fourteen generations, says the text. But we discover that in the final chunk of people, from the exile to Jesus, there are only thirteen generations listed. The text makes a big deal out of telling us that there are fourteen generations. But one generation is missing. The fourteenth generation, the missing one, is the church. It’s us. This is our tree. This is our story. This is our fractured world. These troubled lives are our own, give or take. And this is the story of our own hope, of Christ entering our own lives unexpectedly. Just when we need him the most. The story of a crooked family tree. A crooked people, a crooked church desperately in need. That some how gives birth to world changing hope. And it is changed itself in the process. This is our story. And it’s not over.

So friends, we have reason to rejoice this time of year, though we may reside in darkness. Though we, though the world may know brokenness, hurt and despair. Because this story, our story isn’t over. And there’s still work to do. Advent, Christmas, is not simply about celebrating what has come. The old growth isn’t all there is. It’s about watching for what is coming. Watching for the light in the darkness so we may be light to the whole world. It is about keeping our eyes open for signs of newness. Signs of hope, signs of God’s work in the world. Trusting that even in the midst of our deeply imperfect lives, our own broken and hurt places, there are already green shoots. The Spirit is already at work. Trusting that even in the midst of a world short on hope, that looks out on things and can’t see much of a future, God is coming. And where ever you are coming from, Christ is on the way!

So, ring the bells that still can ring

forget your perfect offering

there’s a crack in everything

it’s how the light gets in.[3]

Amen.

[1] I owe this analysis of Jesus’ family tree to Herbert McCabe’s sermon “The Genealogy of Christ” from God Matters (London: Continuum, 1987), 246-249.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Leonard Cohen, “Anthem.”