Sermon: "Cain, Abel, and Us," June 13, 2021

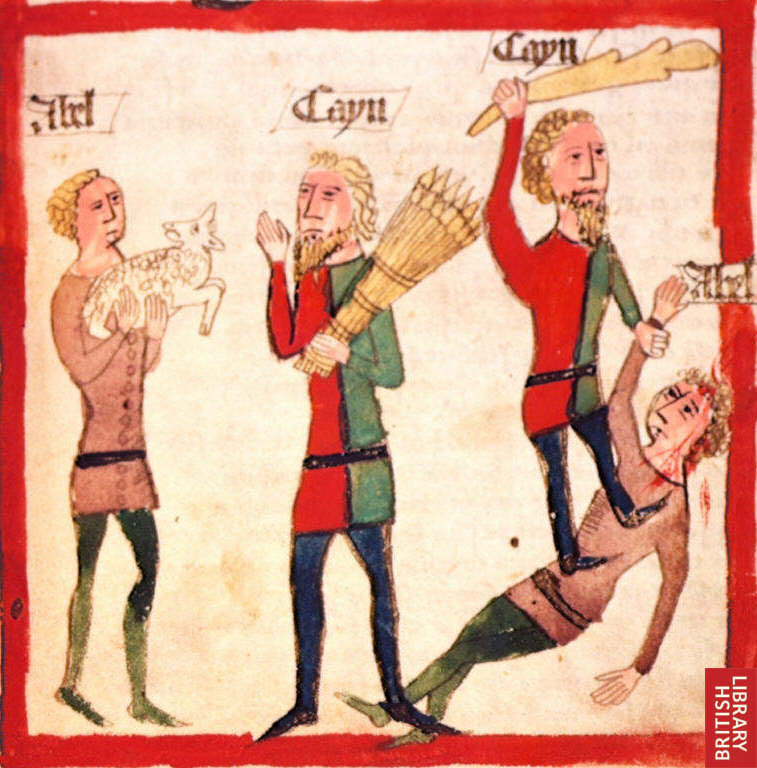

"Cain murders Abel," from from Speculum Humanae Salvationis, Germany, 15 century.

Preacher: The Rev. Ryan Slifka

Scripture: Genesis 4:1-16

Here we are, continuing our sermon series on the book of Genesis, the first book of the Bible. Last week we heard the story of the fall of humanity, of Adam and Eve's eating of the forbidden fruit, and their being cast out of the garden of Eden. With no way to return.

This week we get our first taste of what life's like outside of Eden. It starts out quite lovely, actually. We've got new life, the birth of Adam and Eve's first child—Cain—followed by his younger brother Abel. Especially touching are Eve's words “I have produced a man with the help of the Lord,” as she cradles newborn Cain. She gets at that sense of transcendent wonder and gift of looking into the eyes of our own children for the first time. These children—Cain and Abel—are signs of God's graciousness that continues even though paradise itself has been left behind. It may not be Eden, exactly. But blessing still abounds.

Soon enough, though, the fallen world peeks through, in all its ugliness. One day the family comes together for worship. Each brother a sacrifice to show their dedication to God. Cain’s a farmer and brings a case of vegetables, while Abel, a shepherd brings the “firstlings of his flock,” a prime leg of lamb. Long story short, God—for reasons not entirely clear—prefers Abel’s meat to Cain’s veggies.[i] This sets Cain off. This envy burns so hot in him that Cain figures he's gotta do something about it. And so he invites Abel into the field under the pretence of helping with the harvest. And when his back's turned Cain cracks his brother over the head with a rock, staining the field with his blood. He kills his brother, and God sends him into exile away from everyone and everything he’s known. It all starts with the joy and hope of new beginnings, but then ends with the destruction of a family. The murder of one brother, and the loss of the other forever.

I’ll admit it was hard not to read this scripture without this past week’s headlines in mind. No doubt by now you've all heard the terrible news from London Ontario this past week where a young man—Nathaniel Veltman—purposely hit and killed four members of the Afzaal family, and left their nine-year old in critical condition. The details have yet to be released, but authorities believe that this heinous act was motivated by his hatred or fear of Muslims, and he's charged with four accounts of first-degree murder.

No doubt this young man’s trajectory mirrors that of Cain. Beginning with disappointment, then resentment, then anger, which—unchecked—eventually led to murder. To the destruction of a family, and the wounding of his own family forever, too. And has resulted in his own condemnation and alienation as a murderer. Like Cain, this young man who was once held as a beautiful and wondrous gift in his mother’s arms now will now have to live the rest of his life as criminal. And an outcast on account of the shedding of innocent blood. It’s hard not to see the parallels.

It was heartening to hear how swiftly and forcefully this act was denounced by Canadians of all kinds and all political persuasions. And rightly so. Not only is it a breaking of the law, and a breach of the values that most Canadians hold dear. And from a Christian vantage point it's also direct offence against the righteous and Holy God. One of the worst kind. One which will—like Cain—have life-altering consequences.

As right as we are to condemn this man’s actions, though, we would be amiss if we were just to write this incident off as an irrational, isolated incident of human depravity, that this person is some kind of unique monster. We'd be mistaken if we just leave the story there, and our only response to this event is condemnation. At least as students—or potential students—of sacred scripture.

You see, the story of Cain and Abel isn’t simply about how bad it is to kill innocent human beings. Or about how we shouldn’t murder people in cold blood. We already know this. It’s meant to say something about human nature in general, what it means to live outside the garden.

And this is clear in the short sentences between Cain’s disappointment and the deathly deed. Cain’s face has fallen at the news that his brother Abel’s brought a more perfect platter to the altar. Here God immediately comes to Cain. God, being God, knows Cain’s struggle. God encourages him to move on from this brewing jealousy and hatred. God reassures him that if he does well he’ll be accepted. But God also issues a warning: “Sin,” God says, “Sin is lurking at the door. Sin is lurking at the door, it’s desire is for you, but you must master it.”

Now, we often think of Sin as sins. As the bad things we do. Lie, cheat, steal, murder. These ain’t good, of course. But here Sin is more than that. I love how a Jewish translation puts it “at the tent flap sin crouches and for you it is longing, but you will rule over it.”[ii] God warns Cain that Sin is like the snake in the garden, coiled up in the long grass, waiting for its moment to strike. If he doesn’t watch where he steps, it’ll sink its teeth into him. And that’s exactly what happens. Cain either ignores God’s warning, or doesn’t believe it, and it poisons his family, his life, his future, everything. Here Sin is portrayed as a power that exists outside of us, just waiting for its opportunity to enter in and grab hold. It’s like a gravitational force that pulls us away from God and God’s good purposes. If we don’t keep constant vigilance, it’ll taint everything, everyone we love. Left unchecked it’ll eat us alive.

Now, of course few if any of us sitting in this sanctuary or tuning in online have out and out killed anyone. But like Cain, we’ve all let our small disappointments and resentments grow into anger, and hatred, and more, haven’t we? I’ve certainly known this in my own life, where I’ve let one slight or hurt fester and multiply. How about you? Maybe not to the point of murder, but we’ve certainly let envy, greed, sadness overpower us to the point of wounding others and alienating us from the people we love. We’ve had a taste of it. This is the reason why the New Testament teaches that to hate another human being is on par with murder because it knows the trajectory.[iii] A little seed of resentment may not always grow up into a full blown murder, but it gets that much closer to the point of choking out everything else. If we’re honest with ourselves, we know that given the right circumstances we could end up like this young man who committed this terrible crime.

So we'd be mistaken if our only response to the events of this past week and others like it is only condemnation. If it’s condemnation without self-examination. Because we’re all Cain. Sin lurks waiting for all of us. “If we say we have no sin, we deceive ourselves, and the truth is not in us,”[iv] in the words we were invited to confession with. The same Sin that propelled Cain to kill his brother prowls up and down the hallway of each human heart. The same Sin that drove a young man to destroy a family and strike terror into a whole community loiters at each of our doorways, waiting to lay waste to our lives. We’d be naïve to believe otherwise.

Sounds pretty dark doesn’t it? An endless on-our-toes-or-die struggle against evil. Like God says to Cain, it’s gotta be mastered lest it masters us. Sounds like a bleak and ultimately exhausting way to live. Bad news all around.

As pessimistic as it may be about the human condition, though, there is something that the Bible is optimistic, or hopeful about.

After the murder God exiles Cain to this place called the “land of Nod.” After everything blows up, and he’s sent away from his family his friends, and everything he knows. He can’t even go back to farming because the land is cursed and he couldn’t grow anything if he tried. And I mean, Cain thinks it’s the end for him. He figures it’s a death sentence, that God has turned his face away from him. For good.

But it’s not the case. “Not so!” God says. I mean, there are no exclamation points in Hebrew, so when the translators put one in you’ve gotta really think EMPHASIS. God does this curious thing, the text tells us, and marks Cain. We don’t know what that means—if it was a tattoo on the forehead, or something spiritual that people could just sense by looking at him. Regardless, we’re told that this mark meant that anyone who killed Cain would bring a seven-fold destruction on themselves. Which is to say, nobody would touch him.

Cain, who was consumed by resentment, anger, and hatred. Cain who shrugged off divine warning, killed his brother, and pretended as if he didn’t. Cain who destroyed his family, and blew up his own life. If anyone deserves death it’s him. Even so, he’s sent out with a promise of life. Why is that?

Walter Brueggemann, one of my favourite scholars—my son’s namesake actually—says this. “The protective mark of verse 15 is less than resurrection. It’s less than resurrection, but it is an anticipation of resurrection. It announces that God has not lost interest in the murderer or given up on him.”[v]

As relentless it may be, the Bible seems to believe that there is something even more relentless than Sin. And that something is grace—God’s unmerited, one-unconditional love for sinners. As deep as Cain gets, God goes deeper. As powerful as Original Sin may be, there is an Original Blessing that is all the more so. Christian commentators throughout history have connected God’s marking of Cain with how we’re marked as Christ’s forever in baptism. We’re promised that though we’re sinners, we’re forgiven, broken yet blessed. Though we’re dead to Sin, we’re raised to new life. The Bible may be extremely pessimistic about the human condition, about the all-pervading power of Sin. And yet, it’s also incredibly optimistic about God, and God’s power to overcome it in us.

Knowing God’s grace means that we have no need to resent anyone, anymore. From the smallest interpersonal slight, to the biggest emotional bruise. From our friendliest Muslim neighbors to our most wicked and broken enemies. We have no need to hate anyone anymore, not even a hater worthy of hate like Nathaniel Veltman. We need not give in to fear, or anger of any kind, nor give ourselves over to death because by God we’re given the strength, mercy, and forgiveness to do so.

The truth is that one of the most persistent and powerful mysteries in our lives is the power of Sin. And that in yielding the smallest amount of space in our hearts will lead only to further brokeness and destruction. We know this not only because we’ve seen it in acts of senseless violence, but because we’ve also lived it. It’s not only powerful, and persistent, it’s pervasive. Touching each of us in varying degrees and shades, and ready to pounce at any moment. And yet, the good news is that this is a power that can be overcome, is overcome by the greater power of grace. Sin may lurk at the door, but we can master it, we will master it, because it’s already been mastered in Christ. “Where ever sin abounds,” in the words of the Apostle Paul, “grace abounds moreso.”[vi]

Amen.

[i] A conventional reading of this text has God favouring Abel because Abel gave his best, while Cain held back, meaning that for Cain to “do well” is to give a better offering. While this is a possibility, the better case can be made for ambiguity in God’s reasoning. See Terence Fretheim, “Genesis,” in The New Interpreter’s Bible Commentary, gen. ed. Leander Keck (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1995), 372.

[ii] Robert Alter, Genesis: a Translation and Commentary (New York: WW. Norton, 1998), 17.

[iii] “Anyone who hates a brother or sister is a murderer, and you know that no murderer has eternal life residing in him.” 1 John 3:15.

[iv] 1 John 1:8.

[v] Walter Brueggemann, Genesis: A Commentary for Teaching and Preaching (Atlanta: John Knox, 1982), 65.

[vi] “But law came in, with the result that the trespass multiplied; but where sin increased, grace abounded all the more.” Romans 5:20.