Sermon: "Near and Far," June 14th, 2015 Lord's Prayer Series Week 1

This sermon was given as part 1 of our 4 part sermon series and adult study on "Living the Lord's Prayer." You can find out more about the series here.

June 14, 2015

Third Sunday After Pentecost

Matthew 6:9-13, Luke 11:1-4

"Near and Far"

Rev. Ryan Slifka

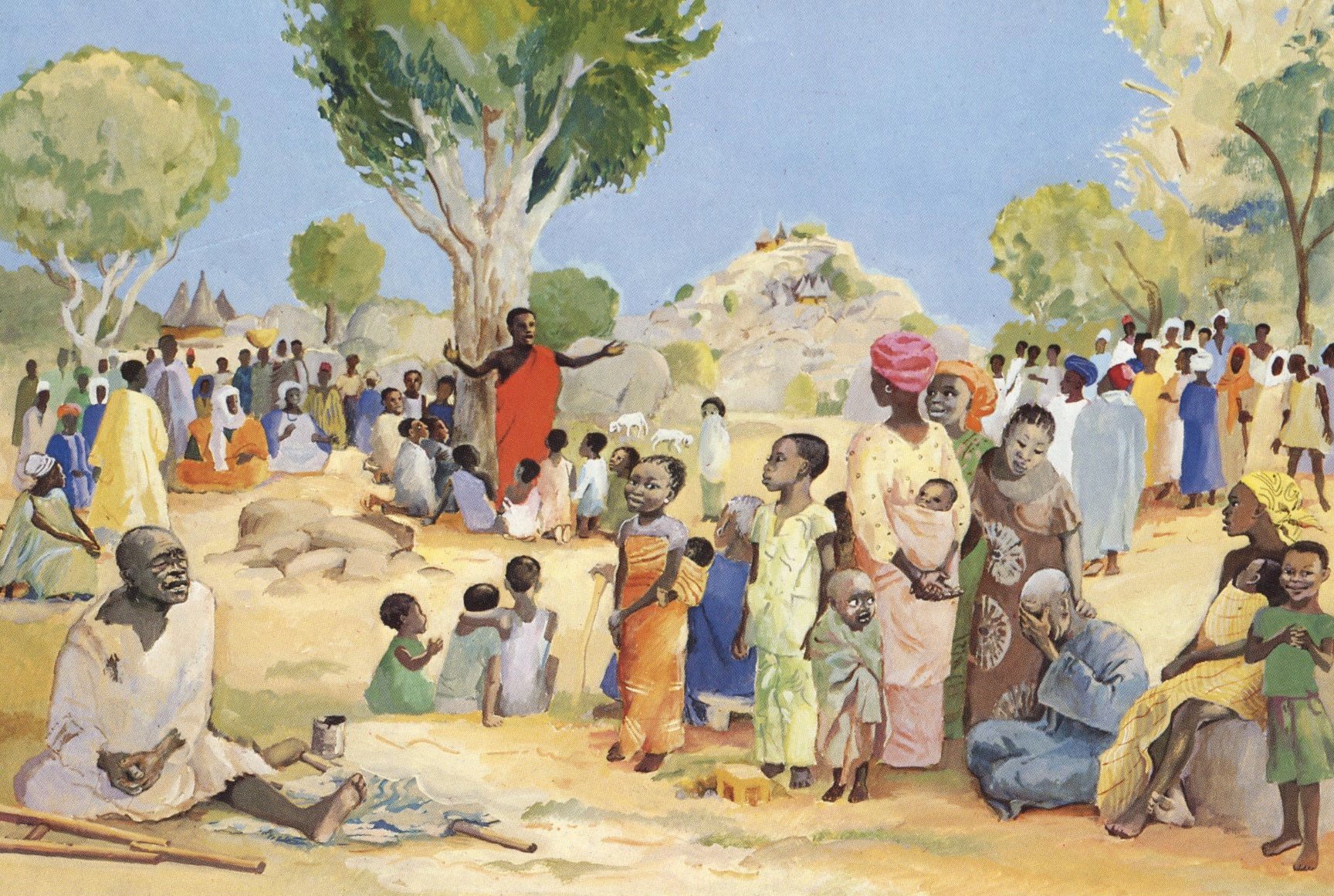

JESUS MAFA. The Sermon on the Mount, from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN. http://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/act-imagelink.pl?RC=48284 (retrieved June 12, 2014).

So, as I mentioned earlier, this morning we'll be hosting the beginning of the Lord's Prayer this morning. The first few lines: “Our Father In Heaven, Hallowed be your Name.” I’ll admit I won’t really go in to deeply about the “hallowed be your name” part, and will be concentrating on the “Our Father, in Heaven” bit. Guess you’ll just have to be a part of the adult study to get it all in!

And, as I mentioned at the beginning of the service, the Lord’s prayer is the way Jesus teaches his followers to pray. So the Lord’s Prayer sets the pattern for prayer. While this is true, it’s not the whole picture. The ancient church used to use a Latin phrase to describe the relationship between prayer and everyday life: “lex orandi, lex credendi.” As we pray, so we believe. Or “the way of prayer is the way of living.” How we prayer and who we pray to paints a picture of how we see God. And it shapes the kind of people we are supposed to be. The great English writer John Stott once said that the whole point of the prayer is to teach us what sort of God our God is. And what sort of priorities a follower of Jesus should have.[1] To put it another way: the prayer offers us a vision of who God is. And what it means to be God’s people. Who God is. And who we are to be.

And so with the first line we learn what sort of God we have. When the prayer begins, “Our Father, in heaven, hallowed be your name.”

God as Father. This is the word that Jesus used to describe his relationship with the divine. That God is spoken of as divine parent. The word “Father” has become difficult for some. Some have grown to see the word as a sign of a larger built-in inequality between men and women. That when God is called “father,” or imaged exclusively as male it inherently reinforces sexist patterns of thinking and behavior that are already deeply ingrained. This can be, and has been the case. And this needs to be taken seriously. Because God is ultimately beyond our human categories of gender (our Father in heaven—which is what we’ll get to). And beyond simple biology of male and female. Not to mention the fact that we miss out on a multitude of feminine images there are for God. Found in the bible itself.

And yet, the point of the prayer is not that God is male. But that the image is one of relationship. A parental relationship. Between one who cares for, loves, guides, and protects their children. And knows them intimately. This means that God is not in some far off place or dimension beyond the clouds. But God is intimate relationship, is involved and active in human life and in the whole of creation. “Our Father.” An immanent presence. One who knows us at the core of our being. A mothering presence. Nurturing, and with us in our joys and in our struggles. Mothering and Fatherly. Caring, as a parent should be. And close as our own breathe.

Yet, God is also figured as “in heaven.” A God who is also transcendent. Ultimately beyond our full knowing and not limited by our joys or our struggles. There is some confusion as to what the scriptures mean by “heaven.” Often, in a way that has been shaped by pop culture, we tend to see heaven as a sort of place off in the clouds that we go to when we die. That is not to say that God’s relationship with us end in death. We affirm, with Paul that nothing shall separate us from the love of God in Christ. Yet, in the scriptures, the heavenly realm is not simply a place where we God when we die. It is the unseen reality of God that is ultimately beyond our full sight and our full knowledge. We “see as through a glass darkly” says Paul. This means that God is there with us in our struggles, but God is not limited by our struggles. God is with us in the present moment, but beyond it. We can imagine a future beyond a dead end we or the world might face in our lives. Because God is not just bound to what we see with our eyes. To speak of God as Father is to speak of a God who is caring, and intimately close, nearby, not in some far off place. Yet, to speak of God as “in heaven” is to speak of a God who is ultimately beyond our full knowing. And our full knowledge. This is, in John Stott’s words, this is “the sort of God we have.”

But what does this all mean? It’s all fine and good to have ideas about God. As I said before, praying in this way is not only about the God we have. It’s also about what it means to follow Jesus. To be God’s people. Our lives are lived out in response to the God we’ve got. It’s about what it means to be the kind of person, the kind of people, who call God our divine parent.

Even the first word means so much. Our. Not “my Father.” Not our church’s Father. But ours. We don’t just have an individual relationship with God. It’s not just about me and my faith. Or me and my salvation. It’s communal. When we pray like this, we join with Christ as our brother, and all the others whom God has named as children. It might be thought of as prayer with all the people of Jesus. But it also may be thought of as a prayer alongside of every human being and all of creation. Because all people, and indeed the whole creation, have been claimed by Gods love. And invited in to relationship with God. God has filed the adoption papers, even if not all have said “yes.”

Here there is a radical equality among people. No one comes to God with any kind of special privilege. None of the categories that divide people, or give them a leg up over other people in our world count before the creator of all things. Not our race. Not our gender or our sexual orientation. Not how much or how little money we may have. Not what we’ve done. Or have had done to us. Whether we are from the suburbs of Vancouver, the streets of Baghdad, or a Cree reserve in rural Manitoba. Nobody owns God. Nobody has a leg up over the other. Because God has drawn intimately close to all people. Because God is the divine parent of all people. And because God has claimed us all as beloved children. This is the kind of people we are to be.

And this is why we do a lot of the things we do as the people of Jesus. The Sonshine Lunch Club soup kitchen, and the St. George’s Pantry offer food and companionship, unconditionally because we believe that we have been made brothers and sisters with all people. This is why we offer deep welcome pass the peace of Christ at the beginning of every service. Because in God’s eyes there’s no difference between a member and a new comer, someone who’s got their life together or someone whose life is in shambles. And this is why Christians since the beginning have believed in the sacred worth of every human life. Because this is how Jesus taught us to pray. And as we pray, so we are. And to become more like every single day.

So, dear friends. Brothers and sisters of Christ. And in Christ. The be a Jesus person is to be a person of prayer. Not just any prayer. But the prayer that begins like this: “our Father…” “In heaven…” The God who we pray to is a God is with us in the here and now. Yet everywhere and always, always beyond our wildest imaginations. To pray like this is to enter into relationship with the God who has claims us as our divine parent. Making us not only beloved children of that parent, but brothers and sisters with each other. And all people through space and time. One that erases the distinctions, things that we use to divide us from each other. And one that invites us in to a whole new way of living. To pray as Jesus prays, and to follow Jesus into the world, is to live in this kind of relationship. Not just with God. But with our fellow creatures. As full equals. God may be ultimately beyond our knowing. But this is who our tradition says God is. And who we are created, and called, to be. Here and now.

AMEN.

[1] John Stott, The Message of the Sermon on the Mount (Grand Rapids: IVP Academic, 1985).